- Home

- Raana Mahmood

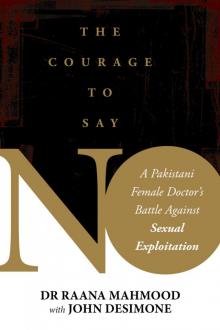

Courage to Say No

Courage to Say No Read online

Copyright © 2019 by Raana Mahmood and John Desimone

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or [email protected].

Skyhorse® and Skyhorse Publishing® are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc.®, a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available on file.

Cover design by Qualcom Designs

Print ISBN: 978-1-5107-4224-6

Ebook ISBN: 978-1-5107-4225-3

Printed in the United States of America.

To the Prophet Mohammed, peace be upon him, who teaches his followers to respect women.

And all those men in the entire world, including my father and son, who respect women.

You don’t get frightened of these furious, violent winds, oh Eagle! These blows only to make you fly higher.

—Allama Iqbal, 786

Contents

Chapter 1: Learning to Say No

Chapter 2: Magic Spells

Chapter 3: Becoming a Doctor

Chapter 4: Reluctant Wife

Chapter 5: Naïve Wife

Chapter 6: Trapped in a House of Hate

Chapter 7: Die in Your Husband’s House

Chapter 8: Seeking Khula

Chapter 9: Who is at Your Back?

Chapter 10: Pretending to Smile

Chapter 11: Second Wife

Chapter 12: The Devil

Chapter 13: Unseen Forces

Chapter 14: Fighting for Taimoor

Chapter 15: The Final Injustice

Chapter 16: A New Direction

Chapter 17: Meeting an Old Acquaintance

Chapter 18: Forced Underground

Chapter 19: A Narrow Escape

Chapter 20: Seeking Asylum

Postscript

CHAPTER 1

Learning to Say No

I FIRST LEARNED OF THE POWER in the word “no” from Father. I was no more than seven years old, sitting in the drawing room of our home in Karachi on a Sunday morning, doing what I was the best at—reading—when I heard voices in the other room. Two men were at the door of our house; they were insisting that they speak to Father, whose name was Mian Mahmood Ali Chaudhry, about an important matter. He greeted them and invited them into the room where I was reading.

On Sundays, we were all at home. My sister worked in the kitchen helping Mother, who never asked me to help in the kitchen, as if she had a sense of impending doom that something bad would happen to me if I were to be around fire or water. On that particular day, I was engrossed in my favorite book, The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes. My brothers were outside playing cricket in the street. Usually, I would be outside too, playing and running with my friends. But earlier, I had brought many books from the Frere Hall library, so I was inside reading.

I loved listening to Father speak about his business. Father never asked me to leave the room when that happened, and now I sat attentively at the far end of the drawing room as he spoke to the two men. Father practiced criminal law, and he often defended men falsely accused of crimes. These men were here to discuss one of his clients, a man who had engaged Father’s services to defend himself against serious accusations. Their voices were low, even friendly. They wanted to convince him to do something. One of the men Father knew already because that man also practiced law. They spoke in familiar tones.

Father was a man of iron will, whom I greatly admired. Father scrutinized his guests with the wary glare of an experienced advocate as I had often seen him do with others. His jaw set, hard as a rock, as he listened. When they were finished, he spoke.

“No, I cannot do that,” Father said without anger; instead, his voice was filled with a determination that he would never acquiesce to their requests. The details of their mission became clear to me as they further presented their arguments. Father was defending a politician against charges of corruption. Father had taken the case only because he believed the man to be innocent. This much I already knew. But these men wanted the fraud charge to stand; they wanted Father to lie in court, or to make his case so weak he could never prevail.

Evil politicians in our government often used false accusations to defame and discredit honest politicians who stood in their way. This way of doing politics was deeply rooted in my country, from top to bottom. Honest people became obstacles to those who unjustly wanted to have their way, so they must be pushed aside.

The men offered Father a large sum of money to prejudice his client’s case, to make sure he did not win. Later, Father told me that the two men offered him more than twelve times what his client had agreed to pay him.

“No, I won’t do that,” he repeated, his voice as firm as ever. He was known as a man of his word. “Don’t you people know that those who give and those who take bribes will go to Jahannum? Now, you must leave my house.”

One of the men laughed brusquely. “Ha Ch. Sahib, you don’t look like a religious person. You have no beard, you wear Western clothes, but you talk about religion.”

“Islam is in my heart,” Father said. “I don’t need to pretend.”

Father rose to his feet. He was tall, toned and athletic, clean-shaven, with neatly combed black hair, and the clear brown eyes that could break stone when he stared at you. Even at home, working in his office down the hall, he wore a suit and tie, because neighbors often came over to ask for help.

It is most unusual for a Pakistani to ask a guest to leave his home, particularly in our home, where hospitality was central to our life. Father had said no to these men’s fraudulent scheme, and now there was no more welcome here. At that moment, when Father insisted they leave, I felt a surge of warmth. I was proud of his courage, of his willingness to stand up to corrupt men. Though I was only seven, I understood the strength it must take to say no. I felt as if I stood on a mountaintop, breathing clean, fresh air.

The men left, and Father closed the front door. He strode by me, through the room, and into the kitchen, where Mother prepared our dinner. There was confidence in each of his steps, his shoulders squared and unburdened; his conscience was not burdened.

A few days later, I was again reading. Mother, the beautiful Ridha, always gracious and kind, settled into the kitchen to cook the family’s favorite foods for the evening meal. She did not ask me to help her in the kitchen, though many of my friends were in their mother’s kitchens learning to cook, helping to clean. Father never allowed me to clean the house, to wash the dishes, and Mother did not want me around the fire we used to prepare food. She wouldn’t even let me open the oven door. She insisted that I see to my books and continue my studies. I was the top student in my grade at school.

Guests arrived at our door, and Mother rushed by me. She ushered several women into the living room, where she greeted guests. They were polite and kind. They had brought her gifts—gold necklaces, gold rings, bangles, and bracelets along with other exquisite jewelry. Their laughter was familiar and inviting, and they were friendly and gracious with their gifts. Mother wanted to know why they would bring her such gifts when she did not like to wear any of this.

In reply

, they asked a small favor of her. She only needed to persuade Father not to help his most important client with his fraud case. It was a little thing, they said, that Father should help them in this way. These visitors wanted her to influence him, to get Father to understand how beneficial it would be for her family if his client lost his case. They promised that their husbands would refer more cases to Father in the future.

Mother was silent. I surmised she considered how she would respond. In her quiet way, she told them she could not do what they wanted. But they were persistent. They laid out many pieces of gold on the table in front of her. One woman placed a few sparkling pieces in her hands, “Ridha, look here. All this jewelry is made of twenty-two-karat gold.”

There was a firmness in Mother’s voice. “I would never ask my husband to lie about anything. I will never go against what my husband has decided. Please take your gifts and go.”

What she did burned in my memory. Women greatly treasure gold. To wear gold necklaces, bangles, and jewelry in one’s hair and on one’s fingers and toes gave one great prestige. And prestige, like appearance, was critical in our society, which was so fractured by ignorance of the teachings of Islam and illiteracy. Mother was unyielding. Their dresses rustled as they rose. They pulled their dupattas over their heads and readied themselves to leave.

Another tried one last time. “Ridha, your neck is very long and beautiful. Look at this necklace.”

Again, Mother said no.

The women left. The door closed. Later when Father arrived home, my parents talked in the kitchen, alone. Father was unhappy that they approached Mother in his absence and his family was in danger from these people. But I never felt in danger. Instead, I felt safe knowing Father was a man of his word and that Mother stood by him, not budging, even for gold and jewels. My parents were true Muslims who could not be bribed or swayed to shirk their duty, even by influential people.

I was very young when I heard all of these conversations; still, I understood what they meant: we must be strong in the face of those who would try to corrupt us. I admired my parents for their loyalty to each other, to their children, and to their religion. From an early age, it was easy for me to see the difference between what was right and what was wrong. There was never an argument in our home over doing the right thing, or treating another person fairly—Father and Mother expected that of us.

Saying no to evil schemes seemed so simple, something that others around us would see as honorable. What I did not know then was how much trouble saying no would cause me as an adult.

Ridha, my mother, grew up in a village in Toba Tek Singh town in Punjab, near Faisalabad City, which was famous for its cotton and textile industry. Mother was known in the area surrounding Toba Tek for her natural beauty, fair skin, long black hair, and pleasant manners. Even though the community had no electricity or running water, education was an essential part of every child’s upbringing. She was one of eight daughters, and even in her simple clothes, her beauty stood out—tall, slim, and with a warm smile, she attracted a lot of attention.

Because of her beauty and sterling reputation, my father’s mother sought her out for a wife for one of her twelve sons. When Grandmother visited her home, Father was already away at college. Grandmother was so taken with the sixteen-year-old Ridha that she proposed an engagement between her and Father right then.

Grandmother summoned Father home from Karachi, where he attended law school, to meet his future bride. Because of her age, Father waited three years for Ridha to finish school.

Father, one of twelve sons, was tall, as were all the men of his family. They were mostly fair, although some had olive complexions, and they were all educated. My paternal grandfather owned a vast tract of land, and while he easily made a lavish living off his property, he wanted a better life for his sons. He and his hired men labored their entire lives on his farm to provide an education for all twelve of them.

My grandfather sent each of his sons to school to nearby Faisalabad, and then on to either Lahore or Karachi for boarding school. My father also studied at the prestigious Aligarh University in Shimla, India. He was forced to leave after the partition, so he came to Karachi and completed his degree at the Sindh Muslim Law College. One of my uncles became a doctor, two were engineers, and several, like Father, became attorneys.

Father’s oldest brother, Uncle Shafi, settled in Karachi where he became a prominent labor lawyer. He was instrumental in passing our current labor laws. Father’s youngest and second oldest brother, who married Mother’s oldest sister, both decided to live with my grandparents in their village.

Father and Mother were married when she was nineteen and he was twenty-six. At that point, Father had a legal practice already established in Karachi. The very next year my brother was born, then I came along two years later, delighting my father.

Father was pleased his second child was a daughter. In our culture, it wasn’t unusual for a man to divorce his wife when she gave birth to a daughter. But not my father. He always showered me with affection and attention, at times more than my brothers, and even pampered me. When I was born, he distributed Ladhu, the customary sweets, in our neighborhood and to the family. He arranged a party for the traditional Gurhty ceremony of placing honey in an infant’s mouth, and for the religious ceremony of reciting of the Azan in the newborn’s ear. As my parents waited for the respectable person they had invited to perform the ritual, a girl entered our house, took up the bowl of honey, and put a dab in my mouth. Mother was stunned this uninvited girl would do such a thing. The guests gasped.

The story behind the Gurhty ceremony is that the qualities and fate of the one who places the honey in the mouth of the infant is transferred to the child. This girl from the neighborhood, Laila, was a college student who had married for love, without her parents’ consent. Her husband was a classmate who was the son of a prominent politician of Lahore. After a few months of marriage, she became pregnant, and her husband disappeared. And now because of her unsavory reputation, no one would have anything to do with her, except my parents, who were always kind to her.

No one knew what she was thinking, barging into the ceremony the way she did, but this incident became an omen to my mother, a portent of what lay ahead for me. For a long time afterward, our neighbors kept asking Mother why she didn’t stop the girl. Mother always took a deep breath of sorrow when asked that question. She did not have an answer.

Shortly after that incident occurred, Mother’s bad dreams began. In them, she saw visions of me drowning in the sea; I shouted and screamed for help that never arrived. Other times, I was trapped in a burning fire, and no one came to my rescue. These dreams reoccurred consistently, frightening her. Though she wasn’t superstitious like so many others, she began to believe them.

I didn’t learn about Mother’s dreams until I was in class two. From my earliest memories, she never allowed me around fire or water out of this dark fear that stalked her dreams. She encouraged me to stay by myself, not to talk to strangers, and not to make too many friends. She feared the people I met could be a danger to me.

With all of her admonitions, I became introspective, studious, and a voracious reader. I visited the library every few days, bringing home armloads of books. I developed an imaginary world, which was fueled by my constant reading. Mine was a happy life, full of characters, adventures, mysteries, and wonderful parents who doted on me. Books became my world.

Throughout my childhood, Mother refused to let me bathe or shower alone, fearing the vision of her dream of me drowning in the sea would come true in our own home. I often joked with her, “Ammi, how can I drown in my own house?”

Consequently, I never learned to swim as a child.

In spite of my Mother’s fears, I was a lively child, friendly with all my schoolmates. I spent my school day laughing and playing with my friends. But I could not have anyone over after school. I always returned home by myself. I felt surrounded by kind and friendly people, but I was alw

ays alone. My favorite companion was my imaginary world.

At the time I didn’t understand her preoccupation with my studies. I thought her instructions to focus on reading was the result of my precociousness as a student. None of her fears stymied my enthusiasm for life. My days were busy with school, and learning, and having fun with my siblings.

Rahat, my younger brother, was my best friend and confidant. We talked about everything, and we were always ready for adventure. Together, we would jump from high roofs and trees to test our strength. My younger brother Rashik was the one I loved the most of my seven siblings. I happily looked after them for mother. My sister Pinky loved me very much.

Many evenings around the dinner table, I was so absorbed in an imaginary world of a story that I continued reading through the entire meal. Often I would forget to eat my dinner. Father would remind me to eat. My siblings weren’t so generous, often ribbing me, trying to break my attention. But it didn’t matter how much noise they made; I kept my focus on the book.

After my father successfully defended that politician against the fraud charges, he decided not to take criminal cases any longer. He started taking civil cases, but then his clients began emotionally blackmailing him to avoid paying his fees. Sometimes, they sent their wives and children to my mother, telling her their reasons why they could not pay their fees. They did not want to pay his charges, and he concluded that many of his clients could not be trusted.

He then took up patent and trademark law, and quickly became a preeminent attorney in his field, working with many international clients who wanted to do business in Pakistan. Once he secured the trademark for a Russian client for tanks and a rifle.

On occasion, he let me accompany him to court. I remember one time in particular. The judge adjourned the noisy courtroom with his command, “Order, order.” When everyone settled down, he heard the case of an old woman seeking justice. It was apparent she was very poor. When he decided in her favor, she began laughing and crying simultaneously from happiness. I remember thinking I should become a judge who could give a fair outcome to people seeking justice. That would be a noble life, one worth working hard to reach. But to become a judge, I would first need to become a lawyer.

Courage to Say No

Courage to Say No